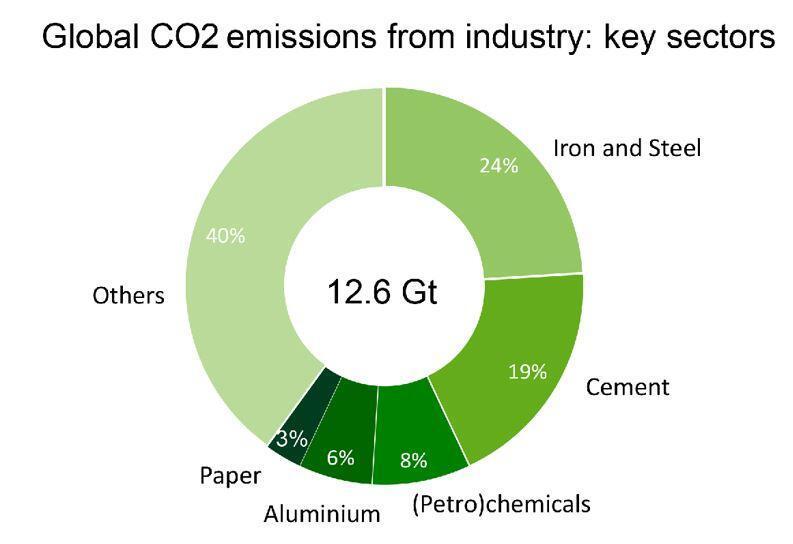

Concrete is one the most utilised construction material in the world because it is strong, readily available, durable, and adaptable. However, numerous studies have shown that can concrete is also one of the most harmful materials to the environment due to its large carbon footprint. The concrete and cement industry contributes to about 8% of the world’s carbon emissions. This therefore reinforces the need for carbon-positive sustainable construction.

According to the Paris Agreement, emissions from iron and steel, as well as cement and concrete and other sectors, must be net-zero by 2050 – 2070 or the owners will suffer the marginal cost of negative emissions at that time.

To achieve net-zero CO2 emissions in these industries, material efficiency must be improved to minimize primary demand for these materials, more and higher-value recycling must be implemented, and production must be decarbonized. As a result, the project team of hotel development in Denver, Colorado, is meticulous about creating and adhering to its carbon budget, because the plans for a new hotel in Colorado call for a concrete structure that is carbon-positive.

According to Grant McCargo, co-founder, CEO, and Chief Environmental Officer of real estate developer Urban Villages, “The built environment, including homes, accounts for 45 percent of the global carbon footprint every year, and as developers, we need to take some responsibility for that impact. Because of this, we made the brave decision to become carbon positive, which means that this hotel will offset more carbon than it produces“.

According to McCargo, Urban Villages is building the hotel with sustainable design and construction elements to stay under its 4,397 MT CO2e structural carbon budget (This equates to the annual energy consumption of 530 houses.)

Exterior of the Hotel

The hotel is being built on a 10,000 square foot triangle-shaped plot of land in downtown Denver, at the junction of 14th Street and West Colfax Avenue. The famous location is next to Civic Center Park, a 12-acre public park encircled by historic government and museum structures, including the Colorado State Capitol.

The hotel will rise 13 floors and feature 265 guest rooms when it is finished, which is expected to be in late 2023. The hotel’s name, Populus, is derived from the aspen trees of Colorado, scientifically known as Populus tremuloides, which are represented on the spectacular front with domed windows.

The first carbon-positive hotel in the United States, according to reports, will be Populus. The project’s carbon-positive objectives will also be helped by a major ecological effort off-site, including a preliminary promise to plant trees equivalent to more than 5,000 acres of forest, according to McCargo. This offset of embodied carbon is roughly equal to 500,000 gallons of gasoline. Urban Villages intends to plant more trees in the future to reduce the energy needed to run the hotel.

A Paradigm Shift in Conventional Design

The initiative got off the ground in 2017 when the city of Denver requested hotel proposal submissions. According to McCargo, his company filed a proposal in an effort to make a lasting impression on Civic Center Park, which was originally created as part of the city’s 1867 bid to become the state capital. Recently, the city invested millions on reviving the park.

According to McCargo, “We appreciated the opportunity to go in and make a huge difference. We were chosen for the project, not because we had the lowest bid, but rather because they trusted us to make a positive change“.

To achieve this, Urban Villages collaborated with renowned architecture firm Studio Gang on a plan that would be both aesthetically pleasing and environmentally beneficial, the latter of which involved completely transforming the location of Denver’s first gas station. The ambitious project attracted Studio NYL, who was keen to take on the role of structural and façade engineer.

According to Chris O’Hara, P.E., founding principal of Studio NYL, “The kind of work that we take on has some aspirational purpose – sometimes it’s performance, sometimes it’s establishing aesthetics.” This project aims to be a carbon-positive building during its lifespan in addition to being an iconic structure in a key location.

The majority of the hotel’s carbon-positive objectives will be met through building operations, but O’Hara points out that a number of structural elements, such as the façade and concrete mix, will significantly boost its effectiveness.

Aerial View of the Hotel’s Roof and Exterior

In order to create a high-performance building and reduce the number of mechanical systems required to maintain it, O’Hara asserts that a tight envelope was crucial. “The main goal for the structure is to reduce the quantity of carbon in the concrete. As structural engineers, we make a great effort to limit material consumption and stick to our carbon budget.

Low-Carbon Concrete

The team decided on reinforced concrete despite its high embodied carbon because of the project’s tight design requirements. According to O’Hara, the site’s geometry, height restrictions imposed by sightlines to the state building, and the square footage all contributed to the necessity of using concrete.

According to O’Hara, “All of these many things made a flat slab concrete system most appropriate to the architecture.” So, the true question was, “How can we take a building with so much cement in it and make it efficient from carbon perspective?”

The team is employing a number of strategies to reduce the amount of concrete in the project in order to achieve that goal. According to O’Hara, these include maximizing slab continuity, positioning columns to benefit from external cantilevers, and reducing column transfers while taking into account the effects on the necessary amounts of steel reinforcement.

According to O’Hara, the integration of the column arrangement and cantilevers with the unit layout and the façade support system are the most crucial components. The design team assessed a range of spacing options and cantilevers to work with the unit needs and mechanical circulation, and how those interacted with the main level and amenity needs, with the goal of reducing the amount of material used.

To stay within the carbon budget, the team will employ low-carbon concrete in addition to keeping the amount of concrete in the project to a minimum. For instance, the use of fly ash lowers the carbon content of concrete, and a minimum of 20% fly ash replacement was adopted in the project. The embodied carbon for each form of concrete placement, such as the drilled piers, walls, columns, flat slabs, was kept to a minimum.

According to O’Hara, carbon sequestration, a procedure that turns carbon dioxide into a mineral that is indelibly incorporated into concrete, could further further reduce the amount of carbon in the concrete. Although carbon sequestration is not yet taken into account in the embodied carbon budgets of the project, but O’Hara believes that incorporating carbon sequestration in their mix design is a top priority for the project team.

Façade Style

The hotel’s envelope will be crucial to fulfilling the project’s carbon-positive objectives, just like the concrete mix is. The facade’s style is pleasing to the eye and is reminiscent of the aspen trees seen throughout the state. According to McCargo, “As an aspen tree grows, the branches fall off lower down with most of the canopy up higher. Where those branches fall off, it makes this charcoal gray eye-shaped eyelet. So, when you look at the facade and think, ‘Wow, look at all of those different windows,’ it’s mimicking what the trunk of the tree looks like, and it creates a fun shape”.

Fenestration

The positioning and design of the windows are meant to lower the building’s energy requirements in addition as producing quirky patterns on the front. The dome-shaped window design also enables self-shading, which further reduces solar gain, according to O’Hara. “We have a truly opaque system with less vision glass than many buildings of this typology, which means our solar heat gain is substantially less,” he says. “Having that vision glass well shaded was a major part in terms of getting improved building performance in Colorado, with the high solar intensity.”

The procedure for fastening the façade to the building is another vital component in attaining the project’s carbon-positive goals. Glass fiber reinforced concrete panels around 20 feet tall by 10 feet wide will make up the façade. The panels will attach at the floor lines every 10 feet with dead weight anchors, as opposed to a standard rain screen that fastens to the structure every 24-48 inches, according to O’Hara. With fewer potential thermal bridges in the façade, he explains, “we can reduce the amount of thermally damaged connections we need.”

Industry Standard

The project team believes that by taking deliberate measures to reduce the amount of carbon in the building’s structure, the hotel will be well-positioned to accomplish the remainder of its carbon-positive goals through building operations. This, according to McCargo, includes composting, off-site renewable energy, and everyday operational effectiveness. When you look at this project holistically in terms of how it will be run and managed, that’s where a lot of the carbon objectives are fulfilled, O’Hara acknowledges, “We can do only so well with a concrete building.”

Although building activities will ultimately turn this project into a carbon-positive one, O’Hara believes that strict carbon budgets like this will eventually become the standard.

Every project that leaves this office is currently undergoing a life-cycle assessment, he says. “We believe that without measurement, management is impossible. As we move through the schematic design, we will begin informing our project partners about the carbon footprints of the various material possibilities, whether or not they want to know. Owners may choose to ignore such information, but it is our responsibility to at least provide them with it so they can make wise judgments.

According to Mere Hall, P.E., S.E., senior associate of NYL Studio, as more developers become aware of this knowledge, it is anticipated that more will take the environmental effects of their projects into account. The major objective, according to her, is to disseminate information so that people may begin having conversations that will advance efforts toward greater environmental sustainability. “I sincerely hope that this becomes the industry norm and a component of the services we offer to advance projects.”