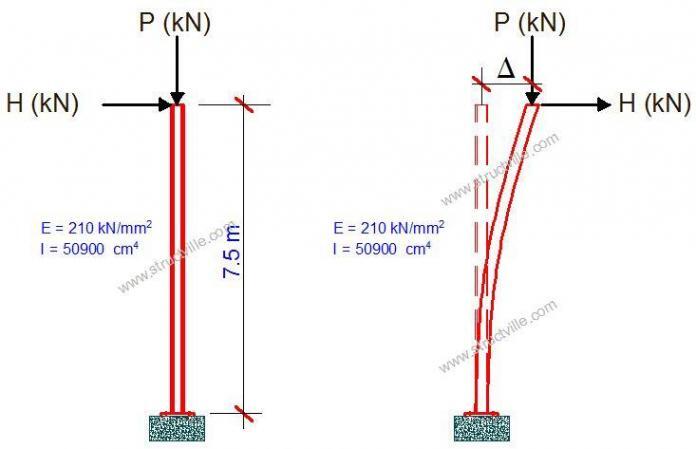

In the design of portal frames and other steel structures, moment-resisting bases can be provided if large lateral forces and bending moments are anticipated. This can lead to the economical design of the frame members, but the base will have to be carefully designed as a moment-resisting connection. Therefore such bases are expected to transfer bending moment and axial forces between the steel members and the concrete substructure. Depending on the direction of the moment and the magnitude, base plates can be symmetric or asymmetric.

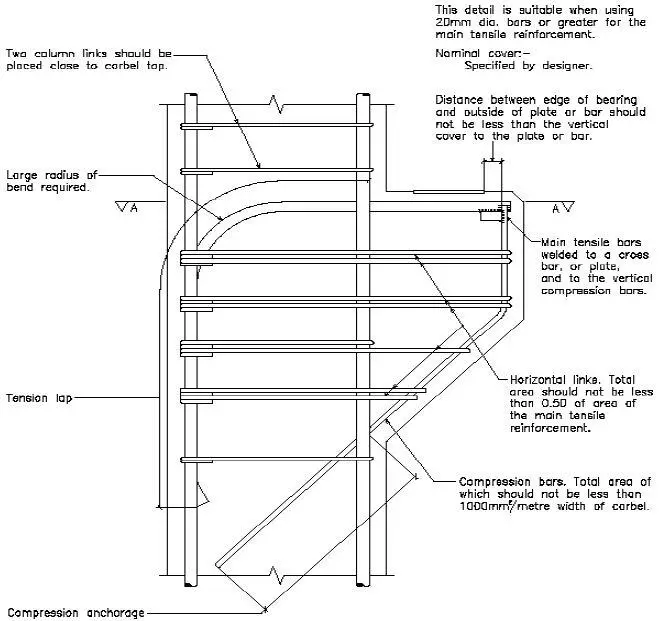

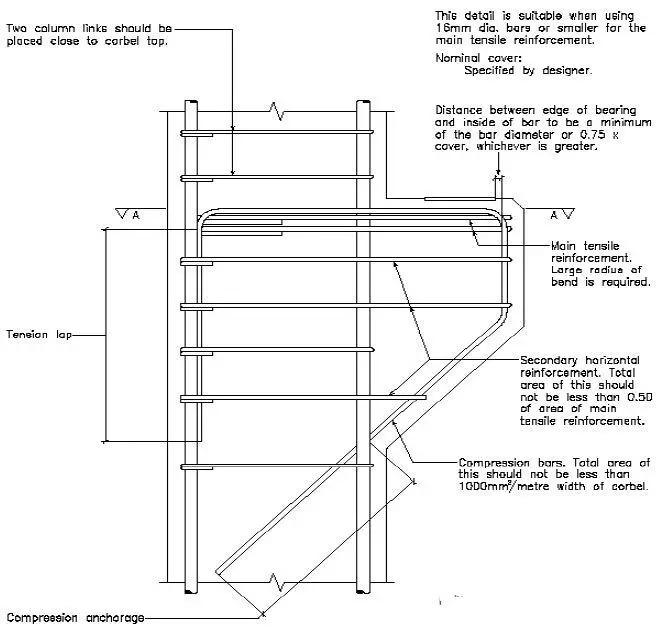

For the design of moment-resisting base plates, the smallest diameter of bolts to be considered should be M20, even though M30 bolts are deemed the most appropriate. Larger bolts in smaller numbers are usually preferable. All holding-down bolts should be provided with an embedded anchor plate for the head of the bolt to bear against.

The sizes of anchor plates are chosen so as not to apply stress of more than 30 N/mm2 at the concrete interface, assuming 50% of the plate is embedded in concrete. When the moments and forces are high, the holding-down system may need to be designed in conjunction with the reinforcement in the base.

Design Methodology

The design methodology for a moment-resisting base plate connection involves using an iterative approach/experience to select the best base dimensions and bolt configuration. This arrangement is then evaluated for its resistance against the anticipated actions from the superstructure.

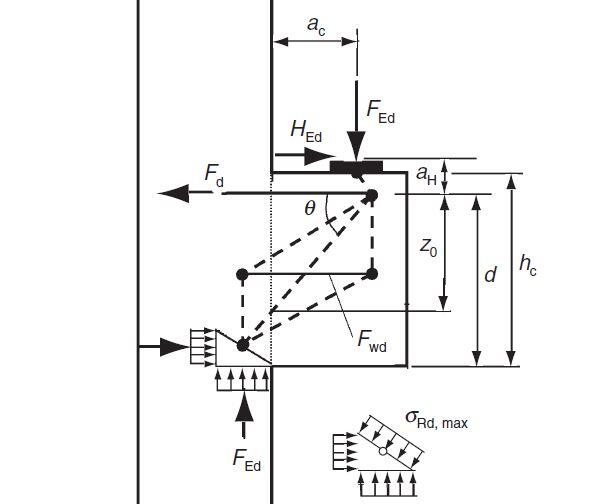

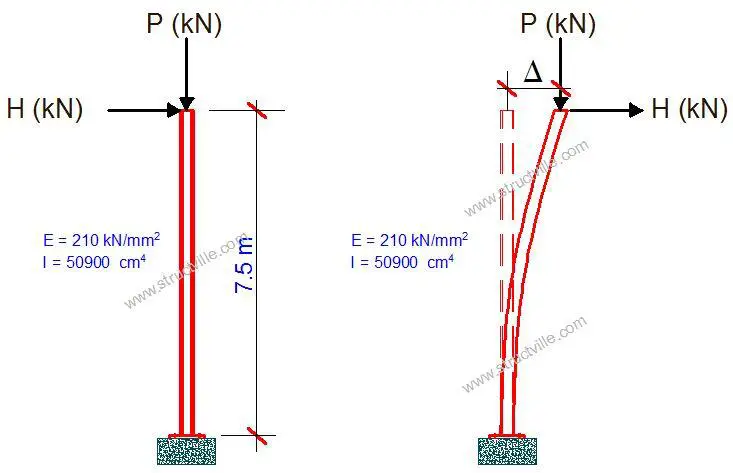

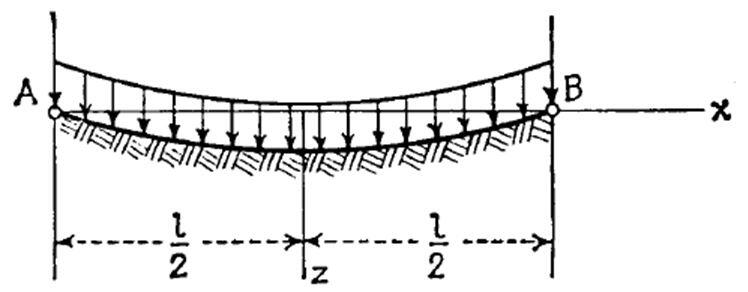

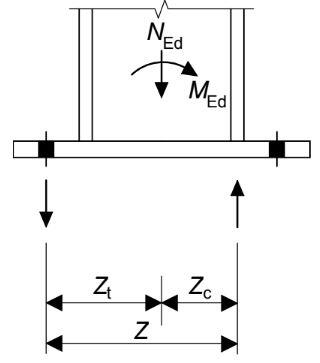

In EN 1993-1-1:2005, the resistance of a base plate subjected to bending moment and axial force is assumed to be provided by two T-stubs, one in tension, and the other in compression. The resistance of the stub in tension is assumed to be provided by the holding down bolts, while the resistance of the stub in compression is assumed to be provided by a compression zone in the concrete, which is concentric with the column flange as shown below.

The design verification of a moment-resisting base plate, therefore, involves the following steps;

STEP 1

Evaluate the design forces in the equivalent T-stubs for both flanges. For a flange in compression, the force may be assumed to be concentric with the flange. For a flange in tension, the force is assumed to be along the line of the holding down bolts.

STEP 2

Evaluate the resistance of the equivalent T-stub in compression.

STEP 3

Evaluate the resistance of the equivalent T-stub in tension

STEP 4

Verify the adequacy of the shear resistance of the connection.

STEP 5

Verify the adequacy of the welds in the connection.

STEP 6

Verify the anchorage of the holding down bolts.

Design Example

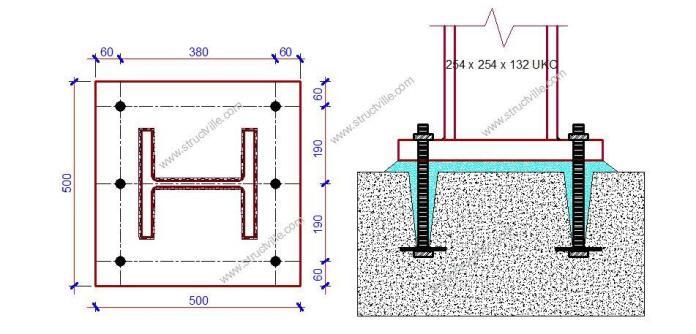

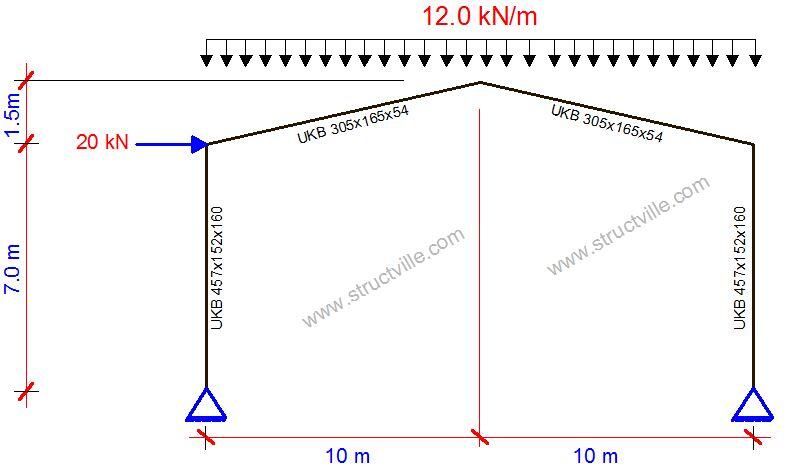

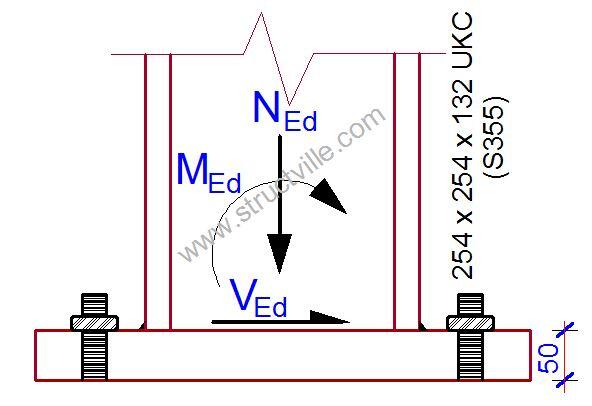

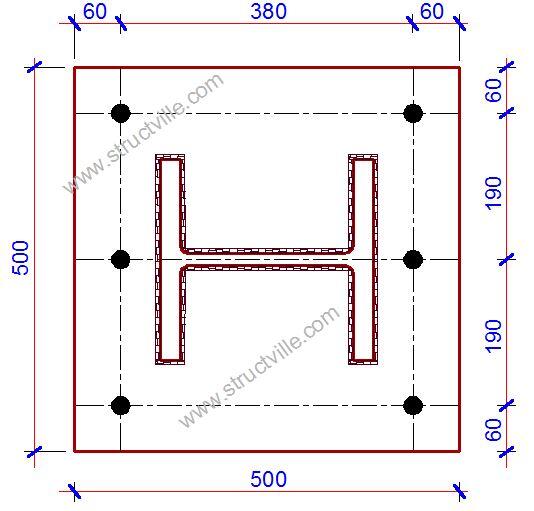

Verify the capacity of the base plate arrangement in grade S275 steel shown below to resist the following actions;

MEd = 125 kNm

NEd = -870 kN (compression)

VEd = 100 kN

Column

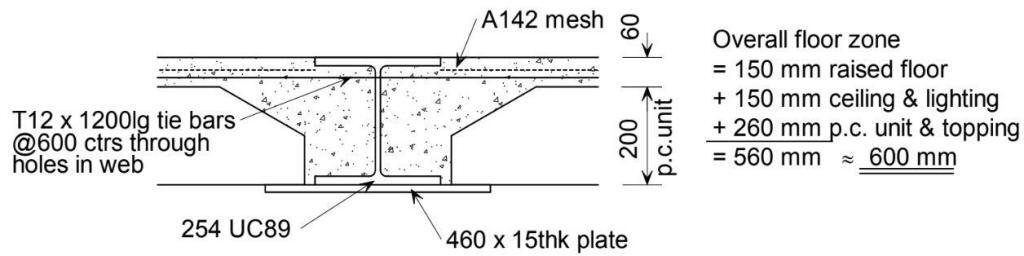

From data tables for 254 x 254 x 132 UKC in S355

Depth hc = 276.3 mm

Width bc = 261.3 mm

Flange thickness tf,c = 25.3 mm

Web thickness tw,c = 15.3 mm

Root radius rc = 12.7 mm

Elastic modulus (y-y axis) Wel,y,c = 1630000 mm3

Plastic modulus (y-y axis) Wpl,y,c = 1870000 mm3

Area of cross section Ac = 16800 mm2

Depth between flanges hw,c = hc – 2 tf,c = 276.3 – (2 x 25.3) = 200.4 mm

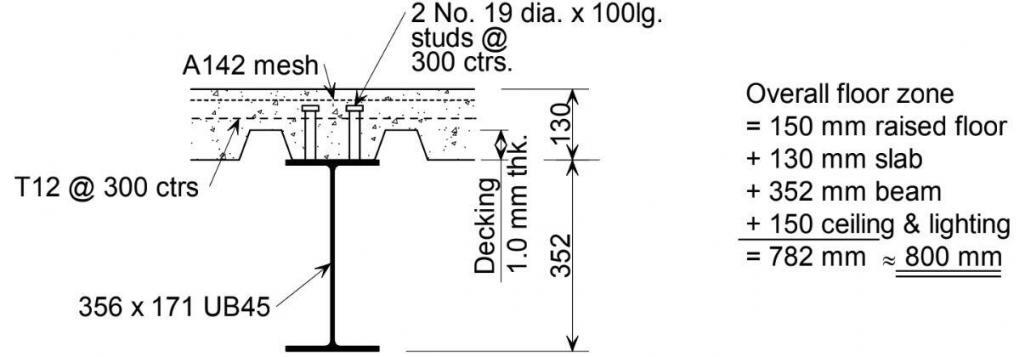

Base plate

Steel grade S275

Depth hbp = 500 mm

Gross width bg,bp = 500 mm

Thickness tbp = 50 mm

Concrete

The concrete grade used for the base is C30/37

Bolts

M24 8.8 bolts

Diameter of bolt shank d = 24 mm

Diameter of hole d0 = 26 mm

Shear area (per bolt) As = 353 mm2

Number of bolts on either side n = 3

MATERIAL STRENGTHS

Column and base plate

The National Annex to BS EN 1993-1-1 refers to BS EN 10025-2 for values of nominal yield and ultimate strength. When ranges are given the lowest value should be adopted.

For S355 steel and 16 < tf,c < 40 mm

Column yield strength fy,c = ReH = 345 N/mm2

Column ultimate strength fu,c = Rm = 470 N/mm2

For S275 steel and tbp > 40 mm

Base plate yield strength fy,bp = ReH = 255 N/mm2

Base plate ultimate strength fu,bp = Rm = 410 N/mm2

Concrete

For concrete grade C30/37

Characteristic cylinder strength fck = 30 MPa = 30 N/mm2

The design compressive strength of the concrete is determined from:

fcd = αccfck/γc

fcd = (0.85 x 30)/1.5 = 17 N/mm2

For typical proportions of foundations, conservatively assume:

fjd = fcd = 17 N/mm2

Bolts

For 8.8 bolts

Nominal yield strength fyb = 640 N/mm2

Nominal ultimate strength fub = 800 N/mm2

PARTIAL FACTORS FOR RESISTANCE

Structural steel

γM0 = 1.0

γM1 = 1.0

γM2 = 1.1

Parts in connections

γM2 = 1.25 (bolts, welds, plates in bearing)

DISTRIBUTION OF FORCES AT THE COLUMN BASE

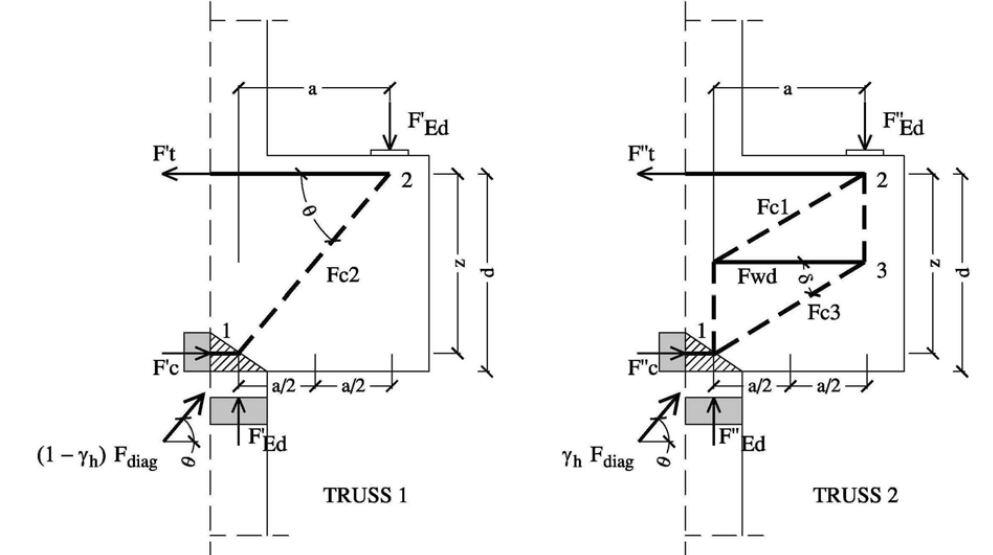

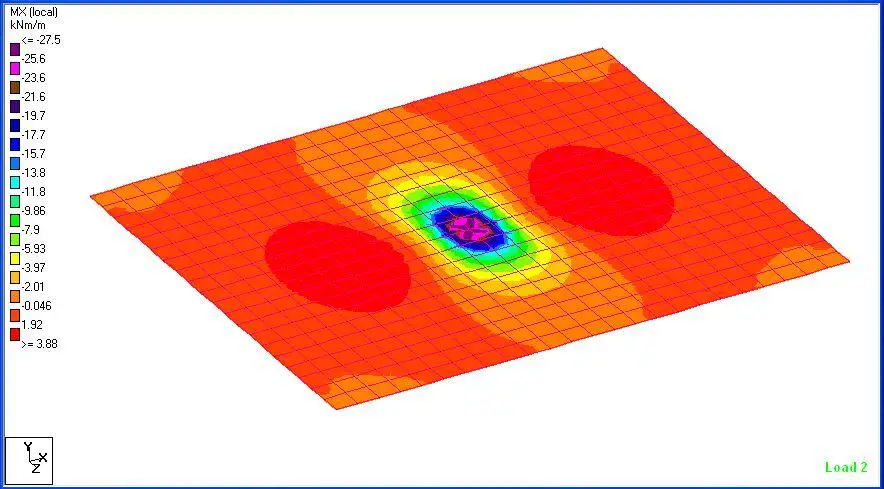

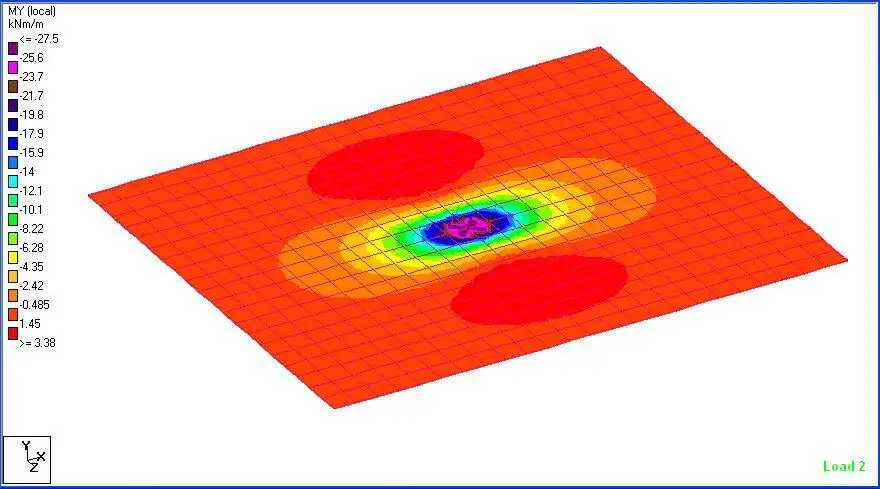

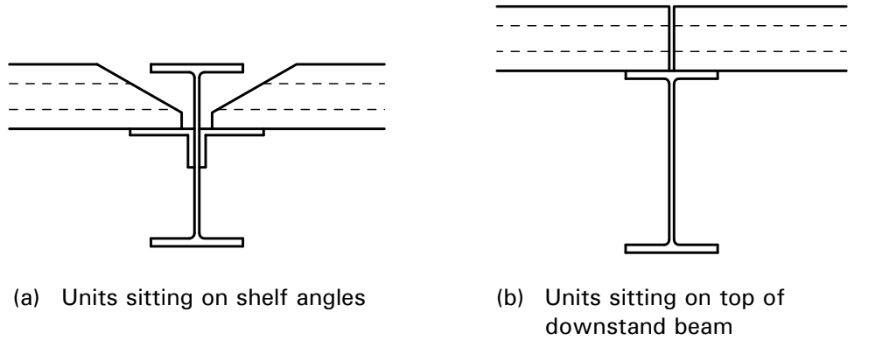

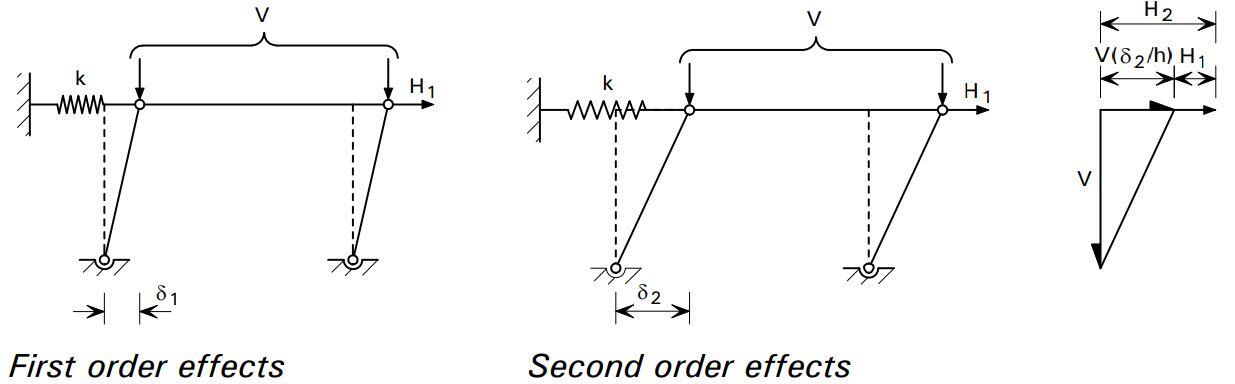

The design moment resistance of the base plate depends on the resistances of two T-stubs, one for each flange of the column. Whether each T-stub is in tension or compression depends on the magnitudes of the axial force and bending moment. The design forces for each situation are therefore determined first.

Forces in column flanges

Forces at flange centroids, due to moment:

NL,f = MEd/(h – tf) = [125/(276.3 – 25.3)] x 103 = 498 kN (tension)

NR,f = -MEd/(h – tf) = -[125/(276.3 – 25.3)] x 103 = -498 kN (compression)

Forces due to axial force:

NL,f = NR,f = NEd/2 = -870/2 = -435 kN

Total force:

NL,f = 498 – 435 = 63 kN (tension)

NR,f = – 498 – 435 = -933 kN (compression)

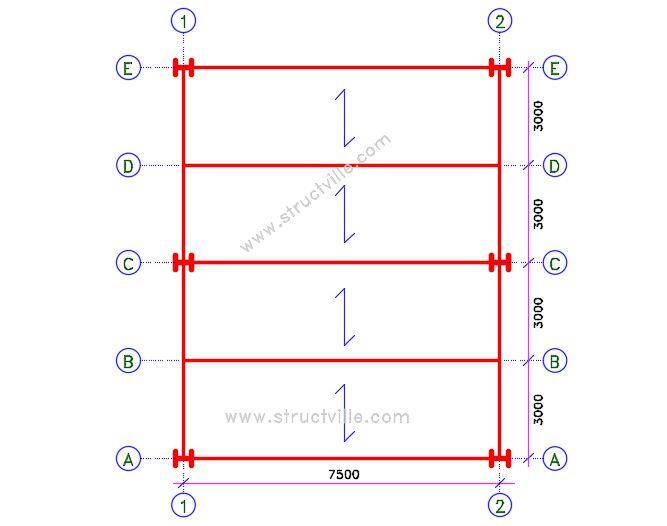

In this case, the left side is in tension and the right side is in compression. The resistances of the two T-stubs will, therefore, be centred along the lines shown below:

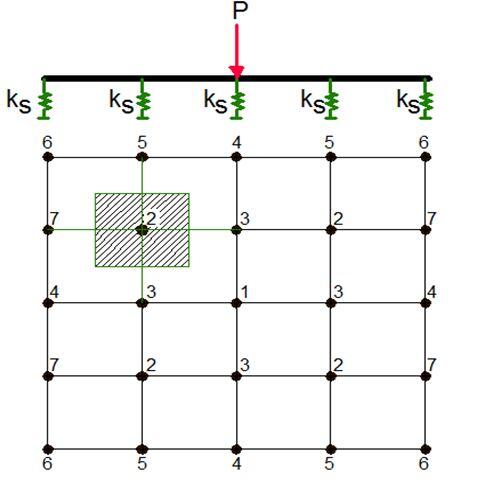

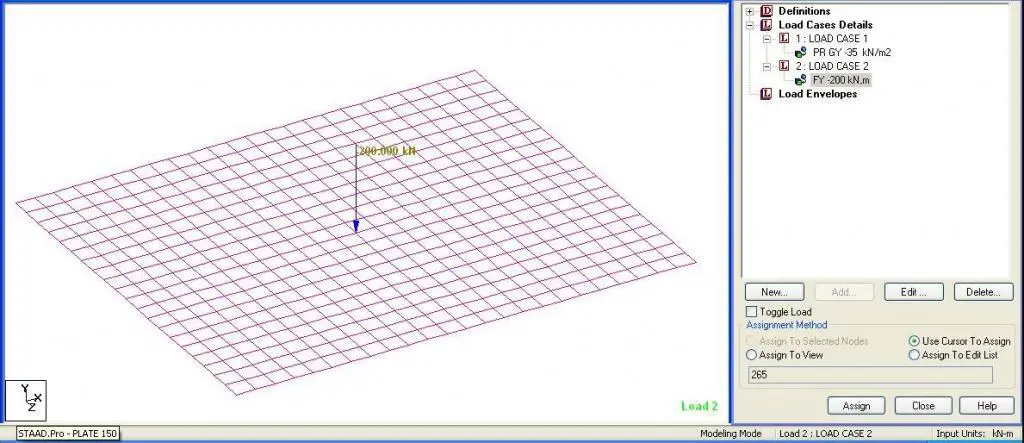

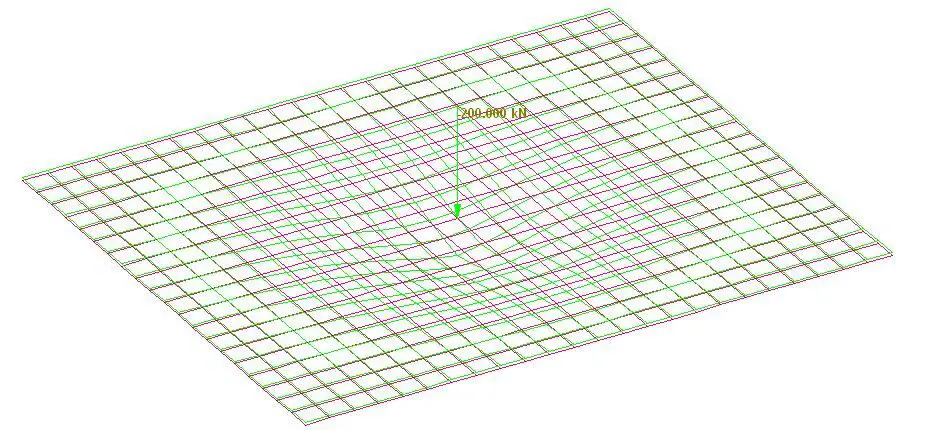

Forces in T-stubs of the base plate

Assuming that tension is resisted on the line of the bolts and that compression is resisted concentrically under the flange in compression, the lever arms from the column centre can be calculated as follows:

zt = 380/2 = 190 mm

zc = (276.3 – 25.3)/2 = 125.5 mm

In this design situation, the left flange is in tension and the right in compression.

Therefore, zL = zt and zR = zc

NLT = [MEd/(zL + zR)] + [(NEd x zR)/(zL + zR)] = [125/(190 + 125.5)] x 103 + [-(870 x 125.5)/(190 + 125.5)] = 50.127 kN

NRT = -[MEd/(zL + zR)] + [(NEd x zL)/(zL + zR)] = -[125/(190 + 125.5)] x 103 + [-(870 x 125.5)/(190 + 125.5)] = -742.265 kN

RESISTANCE OF EQUIVALENT T-STUBS

Resistance of compression T-stub

The resistance of a T-stub in compression is the lesser of:

- The resistance of concrete in compression under the flange (Fc,pl,Rd)

- The resistance of the column flange and web in compression (Fc,fc,Rd)

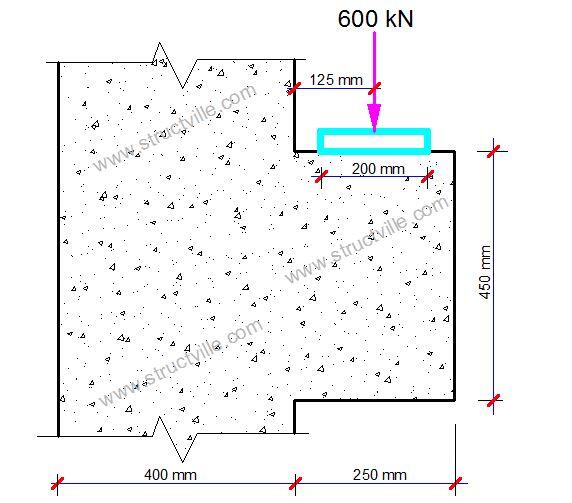

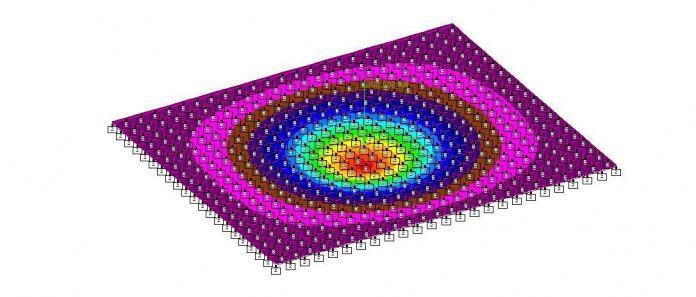

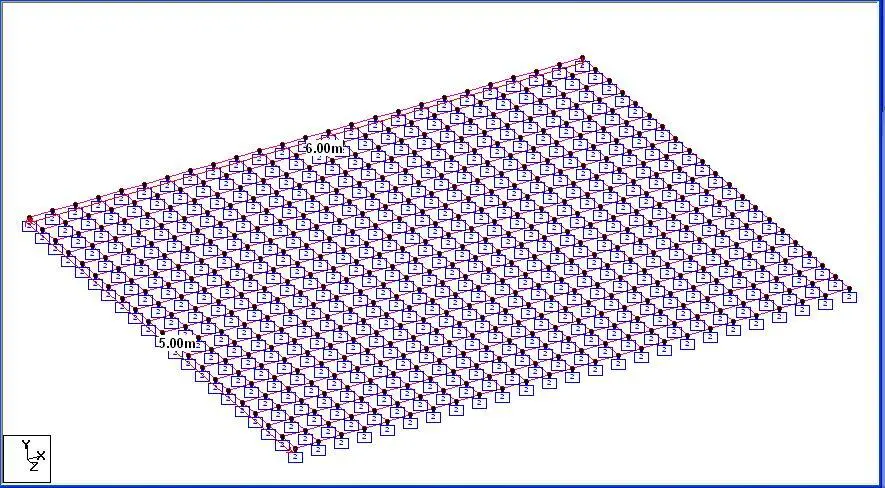

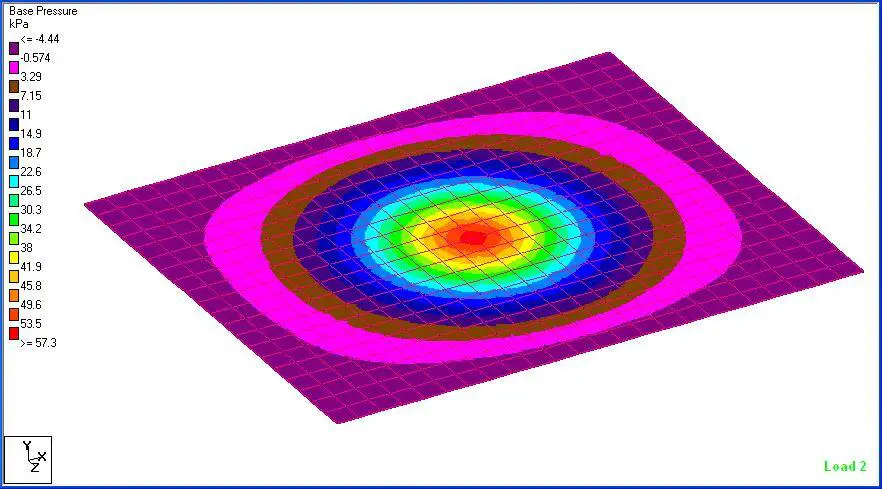

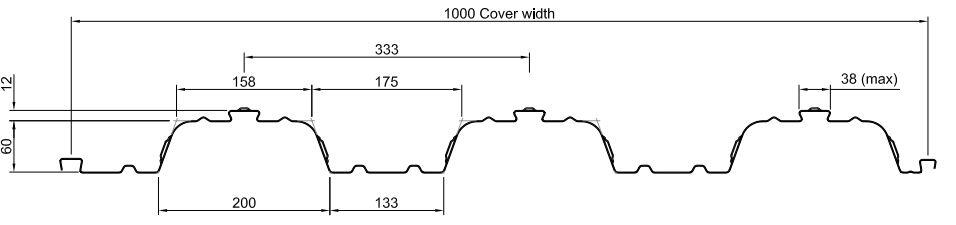

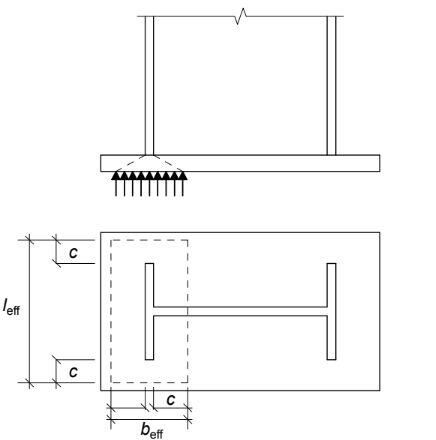

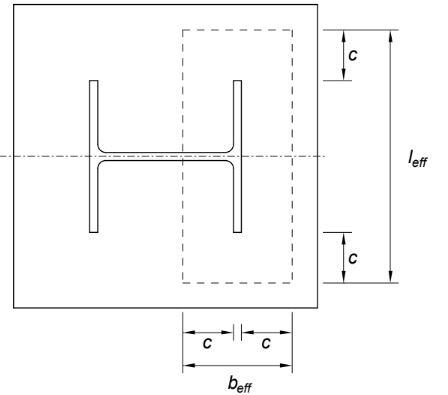

Compressive resistance of concrete below the column flange. The effective bearing area of the joint depends on the additional bearing width, as shown below.

Determine the available additional bearing width (c), which depends on the plate thickness, plate strength and joint strength.

c = tbp x [√fybp/(3fjdγM0)] = 50 x [√255/(3 x 17 x 1.0)] = 112 mm

Thus the dimensions of the bearing area are,

beff = 2c + tfc = (2 x 112) + 25.3 = 249.3 mm

leff = 2c + bc = (2 x 112) + 261.3 = 485.3 mm

The area of bearing is,

Aeff = 249.3 x 485.3= 120985 mm2

Thus, the compression resistance of the foundation is,

Fc,pl,Rd = Aefffjd

Fc,pl,Rd = 120985 x 17 x 10-3 = 2057 kN, > NR,T = 742.265 kN (maximum value).

This is therefore satisfactory

Resistance of the column flange and web in compression

The resistance of the column flange and web in compression is determined from:

Fc,fcRd = Mc,Rd/(hc – tfc)

Mc,Rd is the design bending resistance of the column cross-section = 645 kNm (see page 402 of P363)

If VEd > Vc,Rd/2, the effect of shear should be allowed for

Vc,Rd = 705 kN (see page 234 of P363)

VEd = 100 kN

By inspection:

VEd < Vc,Rd/2

Therefore, the effects of shear may be neglected and hence

Mc,Rd = 645 kNm

Fc,fcRd = [(645 x 106)/(276.3 – 25.3)] x 10-3 = 2569.4 kN

As, Fc,pl,Rd < Fc,fc,Rd the compression resistance of the right hand T-stub is:

Fc,pl,Rd = 2057 kN

Fc,pl,Rd> NR,T = 742.265 kN Satisfactory

RESISTANCE OF TENSION T-STUB

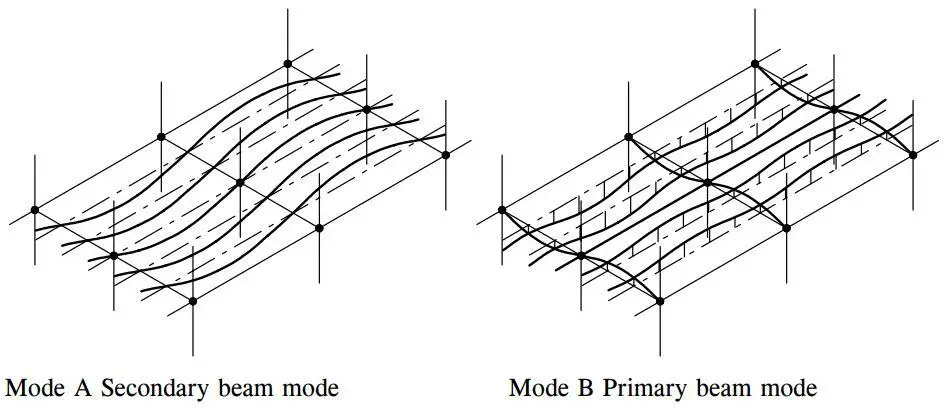

The resistance of the T-stub in tension is the lesser of:

- The base plate in bending under the left column flange, and

- The column flange/web in tension

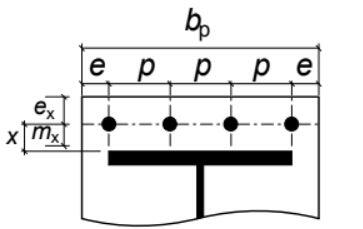

Resistance of base plate in bending

The design resistance of the tension T-stub is given by:

Ft,pl,Rd = Ft,Rd = min{FT,1-2,Rd; FT,3,Rd}

Where FT,1-2,Rd is the ‘Mode 1 / Mode 2’ resistance in the absence of prying and FT,3,Rd is the Mode 3 resistance (bolt failure).

FT,1-2,Rd = 2MPl,1,Rd/m

MPl,1,Rd = (0.25∑leff,1tbp2fybp)/γM0

∑leff,1 = is the effective length of the T-stub, which is determined from the equations below;

bp = 500 mm

p = 190 mm

e = 60 mm

ex = 60 mm

mx = 52 mm

n = 3 (number of rows of bolt)

Non-circular patterns

- Single curvature; leff,nc = bp/2 = 500/2 = 250 mm

- Individual end yielding; leff,nc = 0.2n(4mx + 1.25ex) = 1.5(4 x 52 + 1.25 x 60) = 424.5 mm

- Corner yielding of outer bolts, individual yielding between; leff = 2mx + 0.625ex + e + (n – 2)(2mx + 0.625ex) = 2(52) + 0.625(60) + 60 + 1 x (2 x 52 + 0.625 x 60) = 324.25 mm

- Group end yielding; leff = 2mx + 0.625ex + 0.5(n – 1)p = 2(52) + 0.625(60) + (0.5 x 2 x 190) = 331.5 mm

Circular patterns

- Individual circular yielding; leff,cp = nπmx = 3 x π x 52 = 490 mm

- Individual end yielding; leff,cp = 0.5n(πmx + 2e) = 1.5(π x 52 + 2 x 60) = 425 mm

The minimum is leff,1 = 250 mm

MPl,1,Rd = (0.25∑leff,1tbp2fybp)/γM0 = [(0.25 x 250 x 502 x 255)/1.0] x 10-6 = 39.84 kNm

FT,1-2,Rd = 2MPl,1,Rd/m = (2 x 39.84)/0.052 = 1532.3 kN

Ft,3,Rd = ∑Ft,Rd

For class 8.8. M24 bolts; Ft,Rd = 203 kN

Ft,3,Rd = 3 x 203 = 609 kN

Ft,pl,Rd = Ft,Rd = min{FT,1-2,Rd; FT,3,Rd} = min{1532.3; 609} = 609 kN

NLT = 50.127 kN < Ft,pl,Rd = 609 kN Okay.

WELD DESIGN

Welds to the tension flange

The maximum tensile design force is significantly less than the resistance of the flange, so a full-strength weld is not required. The design force for the weld may be taken as that determined between column and base plate in STEP 1, i.e. 498 kN (NL,f)

For a fillet weld with s = 12 mm, a = 8.4 mm

The design resistance due to transverse force is:

Fnw,Rd = (Kafu/√3)/βwγM2

where K = 1.225, fu = 410 N/mm2 and βw = 0.85 (using the properties of the material with the lower strength grade – the base plate)

Fnw,Rd = [(1.225 x 8.4 x 410) / √3]/(0.85 x 1.25) = 2.29 kN/mm

Length of weld, assuming a fillet weld all around the flange:

For simplicity, two weld runs will be assumed, along each face of the column flange. Conservatively, the thickness of the web will be deducted from the weld inside the flange. An allowance equal to the leg length will be deducted from each end of each weld run.

L = (261.3 – 2 x 12) + (261.3 – 12 – 4 x 12) = 438.6 mm

Ft,weld,Rd = 2.29 x 438.6 = 1004 kN, > 498 kN – Satisfactory

Welds to the compression flange

With a sawn end to the column, the compression force may be assumed to be transferred in bearing. There is no design situation with moment in the opposite direction, so there should be no tension in the right-hand flange. Only a nominal weld is required. Commonly, both flanges would have the same size weld.

Welds to the web

Although the web weld could be smaller and sufficient to resist the design shear, it would generally be convenient to continue the flange welds around the entire perimeter of the column.