A flat slab is a type of reinforced concrete floor system where the slab is supported directly by columns, instead of beams. This system offers many advantages such as reduced headroom, flexibility in the distribution of services, reduced formwork complexity during construction, etc. Strengthening of flat slabs may become necessary especially when openings are introduced.

According to recent research (2021) from the Department of Civil Engineering, University of Wasit, Iraq, openings can be created in a slab after construction in order to pass the new services that satisfy the occupants’ desires, such as water or gas piping, ventilation, electricity, elevator, and staircase. The creation of openings in a flat slab has been found to significantly reduce the structural integrity of the floor.

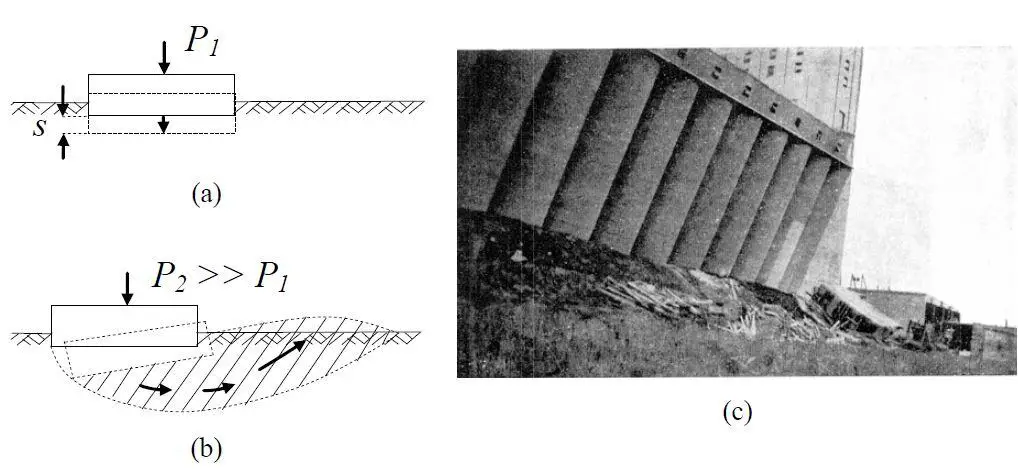

Flat slabs can undergo brittle failure due to punching shear around the columns when the thickness of the slab is insufficient and/or when punching shear reinforcement is not provided. According to Hussein et al (2021), the possibility of punching shear failure increases by creating openings next to the columns due to removing a substantial amount of concrete from the critical section around columns, which is responsible for resisting the punching force. This is usually accompanied by the cutting of several flexural reinforcement bars.

This undesirable impact of openings gets more severe when they are not taken into account during the design, or they are installed after the construction of slabs. The opening influence could be minimized when they are positioned away from the columns, or the slab depth is increased.

From many research works carried out on flat slabs with openings, the following conclusions were reached. The full references and details of the research works can be found in Huessein et al., (2021).

- For openings of the same size, the strength reduction was more significant as the number of openings around the column increased.

- The influence of openings on the strength of slabs is greater when they are constructed in large sizes, especially when the size of the opening is greater than the size of the corresponding column.

- The impact of the opening could be reduced by shifting them far away from the supporting columns. Two far openings were found to be less detrimental than ones adjacent to column’s faces.

- Openings located at column corners reduced the strength of slabs more than openings placed in front of the column

- For openings of the same number and size, the arrangement of openings as the letter (L) around the column caused a lesser drop in the slabs’ punching strength.

In general, the reported maximum reduction in the slabs’ strength due to openings was about 29% relative to the solid equivalents.

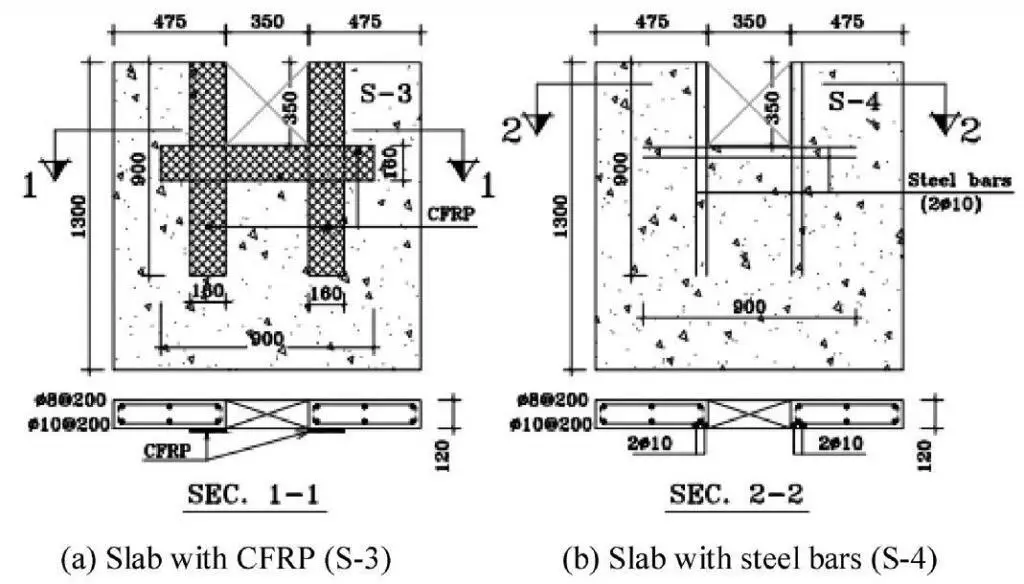

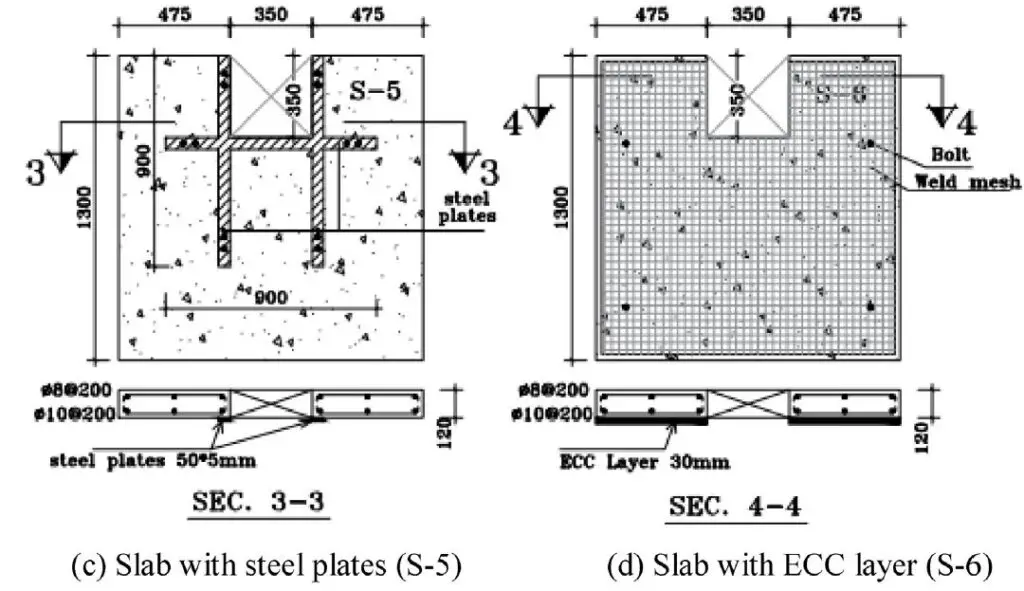

It, therefore, makes sense to strengthen flat slabs with cut-out opening, especially when the effect of the opening was not taken into account during the design. Therefore, Hussein et al (2021) decided to investigate the effects of strengthening flat slabs with cut-out openings using different materials. The strengthening techniques investigated in the study were Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP), steel plates, steel bars, and near-surface mounted Engineered Cementations Composite (ECC) with steel mesh. The findings were published in Case Studies of Construction Materials (Elsevier).

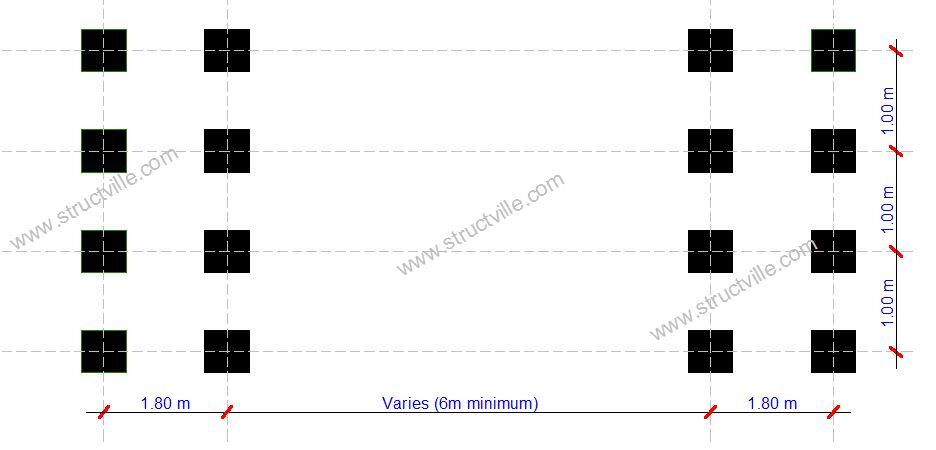

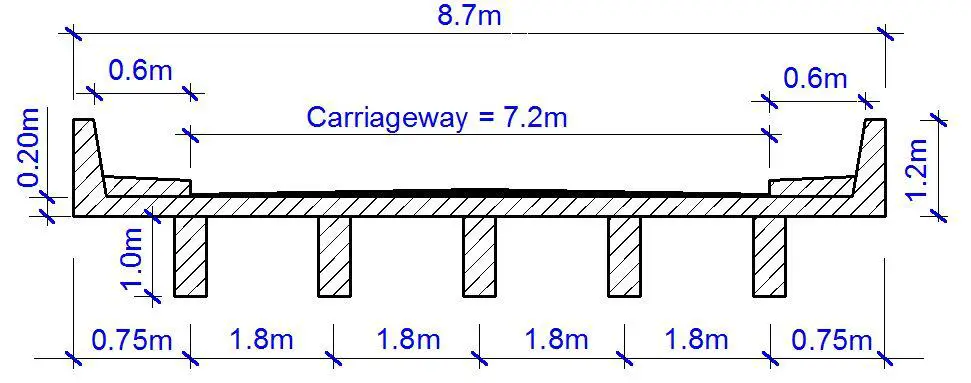

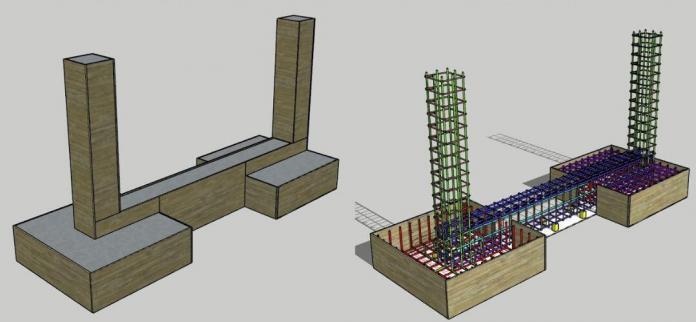

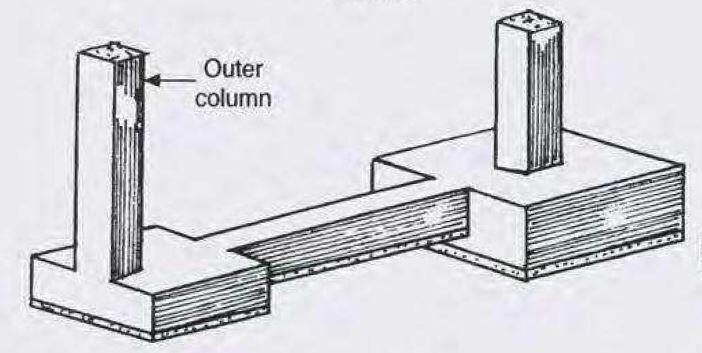

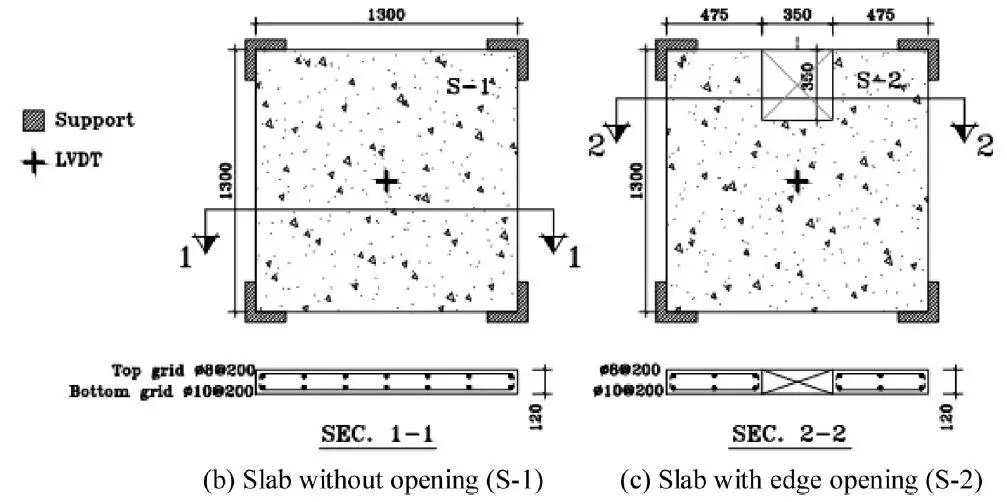

In order to investigate how strengthening can retrieve the lost mechanical strength of slab with openings, six reinforced concrete slabs were prepared with dimensions of 1300 x 1300 x 120 mm. One of them was reference without opening, whereas the others contained a square edge opening of 350 mm side. For slabs with openings, one specimen was the control left without strengthening, and the remaining four were strengthened utilizing various methods stated above.

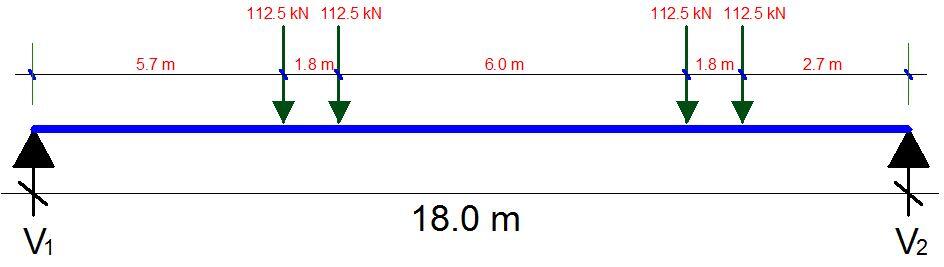

The details of the preparation of the specimens can be found in Hussein et al, (2021). After the curing process completed, the specimens were tested under the influence of uniform loading. The samples were moved into a testing steel rig and rested at their corners on supporting steel plates, measuring 200 x 200 x 30 mm to simulate the real supporting columns. Nevertheless, the rotations around these plates were not restricted. The uniform loading was applied incrementally with the help of a hydraulic jack up to failure.

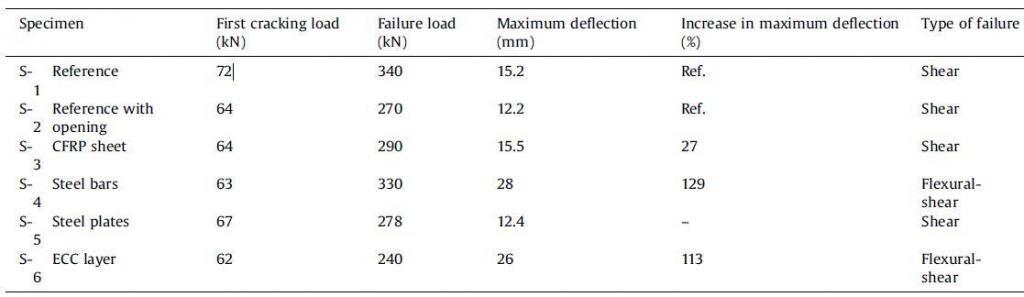

The major results of the experiment are shown below (Hussein et al., 2021);

Based on the experiments by Hussein et al (2021) conducted on six reinforced concrete slabs, including edge openings and strengthened using four various methods, tested under uniformly distributed loads, the following points can be put forward as the essential outcomes;

1. Installation of an opening at the edge of a flat slab resting on four columns and subjected to uniformly distributed load did not change the failure modes. However, the losses in strength, ductility, and toughness were 20.6 %, 16.2 %, and 38 %, respectively when compared with the solid slab.

2. Among the four adopted methods of strengthening, the use of embedded steel bars and EEC altered the failure mode from brittle due to punching shear to more ductile combined flexural-shear modes.

3. The effectiveness of retrofitting techniques in restoring the lost mechanical properties of flat slabs due to openings was found to relate directly to the bond strength between the strengthening materials and the slab surface. Accordingly, the embedded steel bars technique was the most efficient, whereas the ECC was the least efficient method.

4. The strengthening materials should be extended as long as possible from the opening edge in order to achieve a sufficient development length. Hence, the retrofitting materials’ ultimate strength can arrive, and the debonding can be delayed.

5. None of the strengthening methods managed to restore the total missing strength of slabs due to openings. The use of embedded steel bars achieved the most significant upgrading in the slab strength, about 22.2 % over that of the slab with opening and 3 % below the solid slab’s strength.

References

Hussein M. J., Jabir H. A., Al-Gasham T. S. (2021): Retrofitting of reinforced concrete flat slabs with cut-out edge opening. Case Studies in Construction Materials 14 (2021) e00537 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00537

Disclaimer

The contents of the above-cited research work have been presented on www.structville.com because it is an open-access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)